Reading piles of books

On a podcast, Tyler Cowen is asked to recommend some of his favorite books that he recently read.

He avoids suggesting specific ones, and instead describes the broader topics or areas of interest that he’s been studying lately. The history of tennis, for example.

In order to deeply understand a topic he’s interested in, Cowen says he compiles and reads a pile of books on a subject rather than reading a single book. To rephrase an old saying, the pile is greater than the sum of its books.

The concept of reading piles of books is called syntopical reading in Adler’s How to Read a Book. According to Adler’s levels of reading, syntopical reading is the fourth and most difficult level of reading. Instead of only reading one book, many related books are placed into a dialogue inside the reader’s mind, who actively compares and contrasts them.

This sounds like an effective way to learn. I understand something new best when hearing it discussed in different ways or from different perspectives.

But reading a single book is difficult enough. Most good books are hard, and at the very least require a significant investment of time.

Most books are also too long. Tyler Cowen agrees that the essence of most analytical books can be communicated in an article or a blog post, saving hundreds of pages of effort for both reader and writer.

Stretchtext

How can one then expect to read piles of books?

If only there was a way to convert long books into succinct and to-the-point versions of themselves.

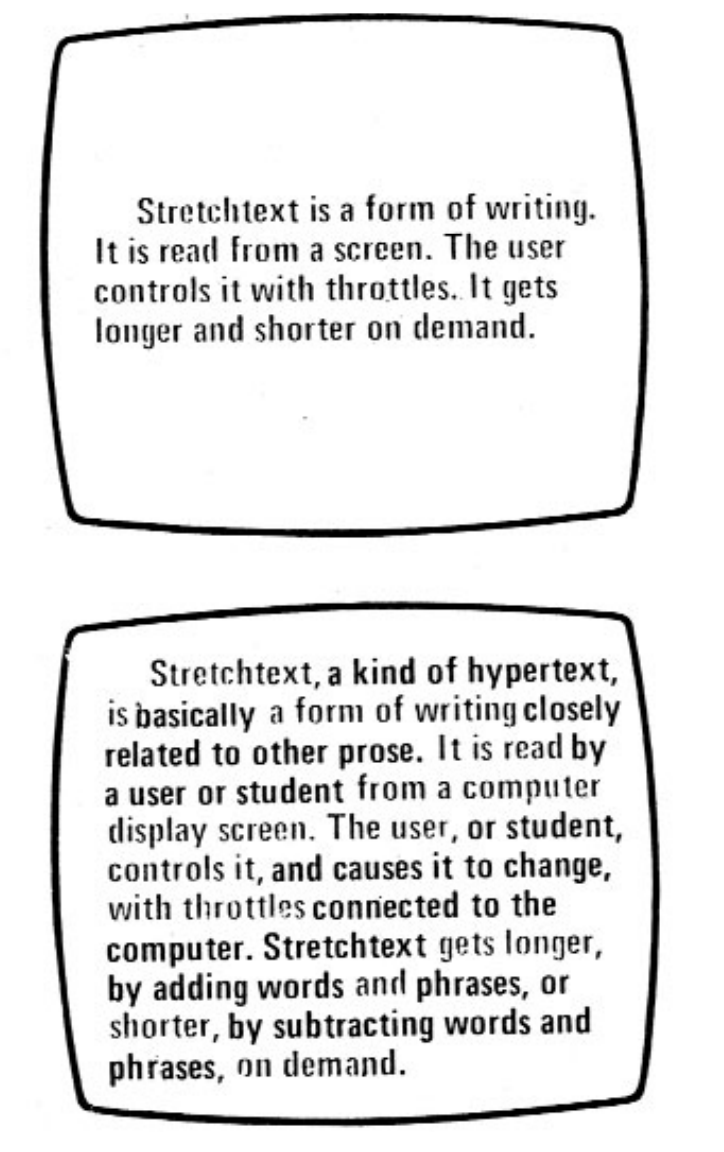

A knob you could turn, kind of like SparkNotes, but on demand, dynamic and catered specifically to you. Letting you dial up, or down, the fidelity on any part of a book you’re curious, or not curious, about.

A device that could shorten, or fast forward through, the books you read, turning them into the equivalent of blog posts or outlines, exposing you to just the parts that mattered, or parts you would be interested in.

StretchText expands or contracts the content in place, giving more control to the reader in determining what level of detail to read at. —Ted Nelson, 1967

This would be great aid for syntopical reading, since you’d be able to process more knowledge with greater efficiency. Instead of spending days or weeks getting one dense perspective by a single author, you can read many books in that same amount of time, getting many perspectives from different writers.

No such technology exists that I know of yet (Stretchtext was just an idea), but below, I outline some techniques to get more out of books, faster and with less effort.

How to read a book

This idea of skimming or extracting the core idea of a text is central to the reading techniques described in the seminal How to Read a Book by Adler.

Adler says that not all books should be:

- read

- read in full

- read at the same speed

Some books, on the other hand, may need to be:

- read fully

- read very slowly

- read multiple times

Therefore, a reader should be able to dynamically alter their reading style based on the difficulty of a work before them, how much time they have to spend with it, and what they want to get out of it.

One of the reading techniques described in the text is called “inspectional reading”. Rather than forcing one’s way through a book page by page, cover to cover, a reader instead starts by spending a brief amount of time to “inspect” the book at hand and extract its structure and main arguments to create a sort of map.

One skims the work with the goal of uncovering the skeleton (outline) the author has created in order to present the arguments (organs and flesh) of the book.

Inspectional techniques include paying attention to certain things.

The choice of title and subtitle. The chapter names and their ordering. The introduction’s exposition of the main thesis and supporting arguments. The topics enumerated in the index or sources cited in the bibliography.

Diminishing returns

At what stages of interaction with a book do you get the most out in relation to the effort put in? When do you approach diminishing returns? When is it time to change your approach or to stop reading the book altogether?

The initial curiosity that gets you interested in even considering a work is likely the highest return for the least effort. I personally indulge in constantly adding books to an endless wish list on Amazon, which now counts in the thousands. I know I’ll never read most of them, but I learn from considering them and looking them up.

Imagine you heard that Thinking, Fast and Slow explains how human cognitive biases impair their daily judgement. Reading only a blurb quickly puts the big idea in your mind, with a high-level understanding of its implications. If someone mentions cognitive biases at a party, you have at least a high-level sense of what they’re talking about.

Kahneman’s book is fascinating. But it is an exhaustive treatment of the topic that can be tedious to read. Inspective reading allows you to get the most out of a book with respect to the amount of time you have to devote to it.

Using a your limited free time to get a sense of the entire arc of a thesis and its supporting arguments by skimming is more useful than only getting through the first few chapters when attempting to read something from cover to cover.

Extracting structure

Effective written communication follows a pattern and most descriptive works are written using a common structure. Practicing identifying the structure makes extracting the main ideas of a book easier and quicker.

Typically, introductions at the beginning of expository books summarize the central arguments and structure of the text succinctly.

Next time you plan to read something, instead of reading a long blog post or New Yorker article, try reading the introduction to a book you know you aren’t ready to devote to reading in full. After reading a good introduction, you’ll have enough familiarity with the ideas of the book to hold a high level discussion on it, and, more importantly, to have it influence your thinking.

Authors often employ other standard structures. Chapter titles describe the main idea of the chapter. Chapters begin by introducing the main argument of that chapter. Skimming the first few sentences usually gives you a good sense what it is about. Chapters end with concluding remarks and a summary of the chapter. Reading both is a quick way to get a sense of the content.

Individual paragraphs work in a similar way on a zoomed in scale. Paragraphs have topic sentences, etc.

You can skim a chapter by quickly reading the first sentence and last sentence of every paragraph, spending more time in sections you find more important or interesting. And so on.

A road trip without a map

Reading absent-mindedly from cover to cover is like driving without a map. If you’re driving across the country from New York City, you know Los Angeles is somewhere west and you’ll probably get there if you just start driving west. But why not prepare for your trip? With minimal effort, you can learn the distance of the journey ahead of time, what cities you’ll have to stop in, what the weather is in different areas, and what supplies you’ll need to bring.

Understanding the structure of a book ahead of reading it also gives you a map to guide you on your reading quest. It lets you anticipate what’s next, giving more context and understanding to the section you’re on now. It keeps you from getting bored, because you can speed up your reading to get to a more interesting topic that’s coming ahead.

Sometime soon, machine learning will likely make something similar to Stretchtext a common feature to all digital readers. Until then, we can learn more by reading piles of books better and faster by using age-old reading techniques.